Are you steamrolling your teams?

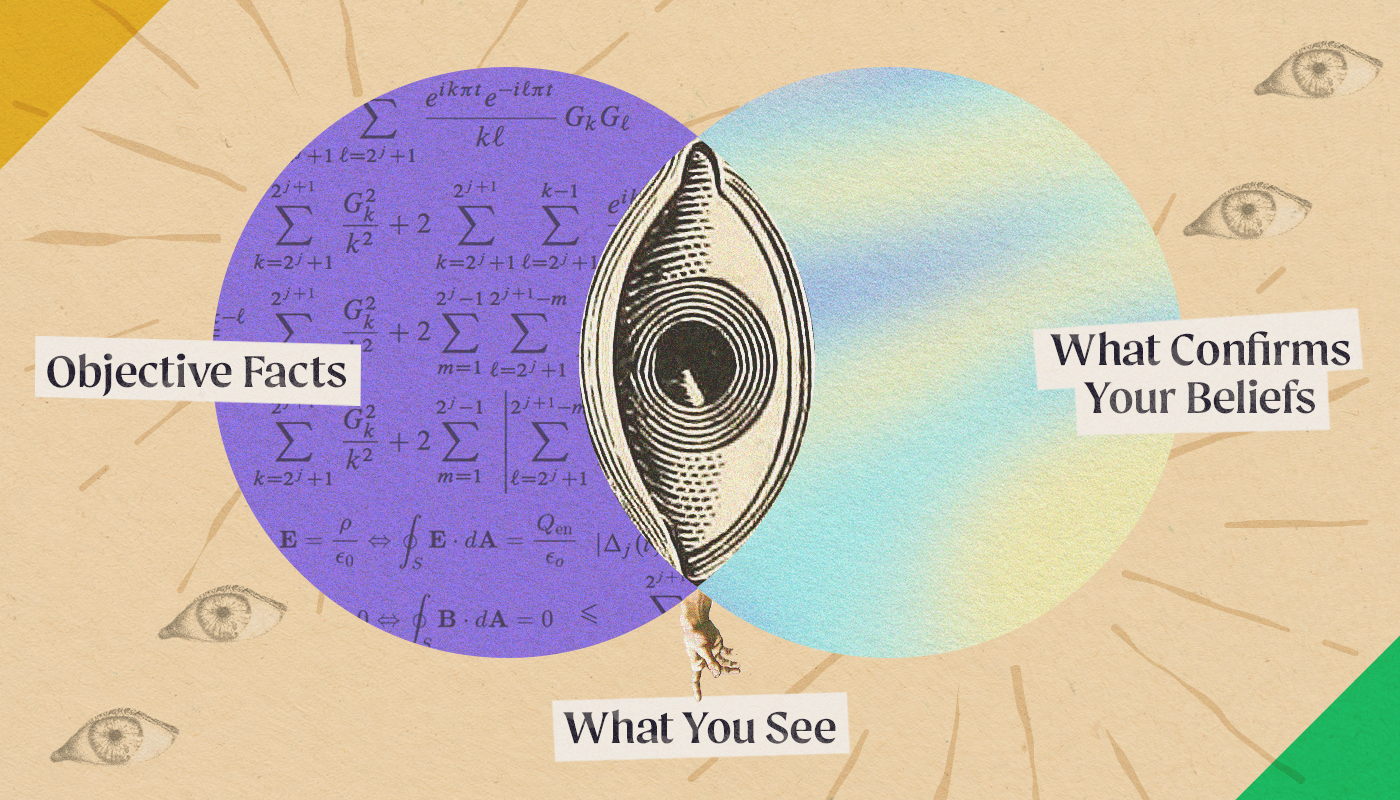

How to counter confirmation bias.

The Slack ping caught Beth’s* attention on a typical Tuesday afternoon. The request was from her manager: “Hey— Can you each come up with design ideas to pitch tomorrow?”

Story from interview with Beth* an LA-based associate at a design firm.

Despite the late notice, she quickly reprioritized her already tight schedule to mock-up several website concepts, complete with a heavily researched guide. She worked late and knew the things she had set aside to meet this request would be equally demanding tomorrow.

The next day at the meeting, the designers went around sharing their concepts. Most involved engaging features on the website, a desire requested by the client. Beth pitched a design with micro-interactions to also intuitively guide users through the page. The manager was pleased, “Well done! These are great ideas, and you’re exactly right. Let’s take an information-driven approach and unpack all the statistics so people can read it.” Her manager went on to describe a copy-heavy idea completely contrary to what she just pitched— an idea that he seemingly had all along. While her boss attributed the final product to her, it was barely similar to what she had initially proposed.

Beth wonders ![]() “Does he ever listen to our contributions, or does he just parse through them to support his own?”

“Does he ever listen to our contributions, or does he just parse through them to support his own?”

Confirmation bias, explained

What Beth is describing is called confirmation, or myside, bias— a cognitive bias stemming from people favoring information in a way that confirms their preexisting beliefs. Her manager, excited and confident, cherry-picked from the team’s input to reinforce the validity of his own idea, steamrolling over the team’s input in the process.

The term “confirmation bias” was first coined in 1960 by a cognitive psychologist, Peter Wason, though evidence and discussion of it can be found much earlier.

Wason’s Rule Discovery Test

Known as Wason’s Rule Discovery Test, the experiment examined the extent people test their own hypotheses. Participants were asked to identify the rule that applies to a series of three numbers. Given the numbers “2, 4, 6” as an example of the rule, the participants were asked to find the rule by making their own sets of numbers to see if they too satisfied the rule. The experiment showed rather than test for sets that disproved the rule, participants formed a hypothesis and tried sets that would only prove it.

Years of studies, including more recent experiments, also indicate that people are generally less critical of their own arguments and seek out information to support their position, displaying a confirmation bias.

The danger of mental shortcuts

Like many cognitive biases, confirmation bias acts as a cognitive shortcut to make gathering and assessing information easier. These shortcuts fall into System 1 thinking, the gut reaction, fast way of processing our surroundings. Conversely, System 2 is the analytical way of processing information. As described in Thinking, Fast and Slow reader’s blog post, “One of the biggest problems with System 1 is that it seeks to quickly create a coherent, plausible story — an explanation for what is happening — by relying on associations and memories, pattern-matching, and assumptions.”

Slow your roll

In order to be better collaborators and more inclusive people, we must look more closely at the information on which we’re basing our beliefs and how that affects not only us but the people we work with. Deeply understanding confirmation bias will help you realize you can’t do business without bias influencing your work. To be proactive in addressing cognitive biases requires you to slow your thinking and unpack the shortcuts you’ve been taking.

We are all socialized in a society with systemic oppression: racism, sexism, classism, heterosexism, ableism, ageism, religious domination, and more. This oppression gets INSIDE of us – it shapes us – our thoughts, feelings, behavior. 3/

— Shimon Cohen (@ShimonDCohen) June 2, 2021

Rather than saying “check your bias at the door” we need to acknowledge how these systems live in us & how they show up in our work. This connects to our positionality-our power, privilege, & oppressed identities-in relation to larger social, political, economic structures. 4/

— Shimon Cohen (@ShimonDCohen) June 2, 2021

So for me, I want to bring this analysis INTO my work, not leave it at the door. Of course I want to make sure I am not discriminating. But “checking bias” does not mean discrimination will not happen. Or that anti-oppressive/liberatory/justice-based practice will happen. 5/

— Shimon Cohen (@ShimonDCohen) June 2, 2021

Shared by anti-racist social work educator on Twitter

To counter your own confirmation bias, or a colleague’s, try these tricks:

1. Consider the opposite: What are some reasons that your initial thinking might be wrong? This technique works because it explicitly directs your attention to information that wouldn’t otherwise be considered.

2. Break out of the echo chamber: Do the only people you follow on Twitter look just like you? Online media platforms feed information tailored to your interests and beliefs, strengthening confirmation bias. Actively seek out and engage in a variety of quality content that may be contrary to your views to diversify media algorithms.

3. Be honest with yourself in meetings: Are you looking for a new idea or self-validation? Instead of leading questions, if you’re really open to ideas, ask open-ended neutral questions to cultivate new possibilities. For example, rather than asking, “Do you think this is a good idea?” ask, “What are the strengths and weaknesses of this approach?”

4. Devil’s advocate: What is missing from this conversation? Don’t get us wrong— Playing “the devil’s advocate” gets misused all the time to derail otherwise meaningful conversations. However, dedicating time while decision-making to thoughtfully discuss other points of view as a team relieves any one individual from challenging the steamrolling.

5. Speak up: What aren’t they hearing? If an idea you shared was cherry-picked and misconstrued, clarify to the group your point of view, clearly distinguishing the crucial information that hasn’t been taken into account. ![]()