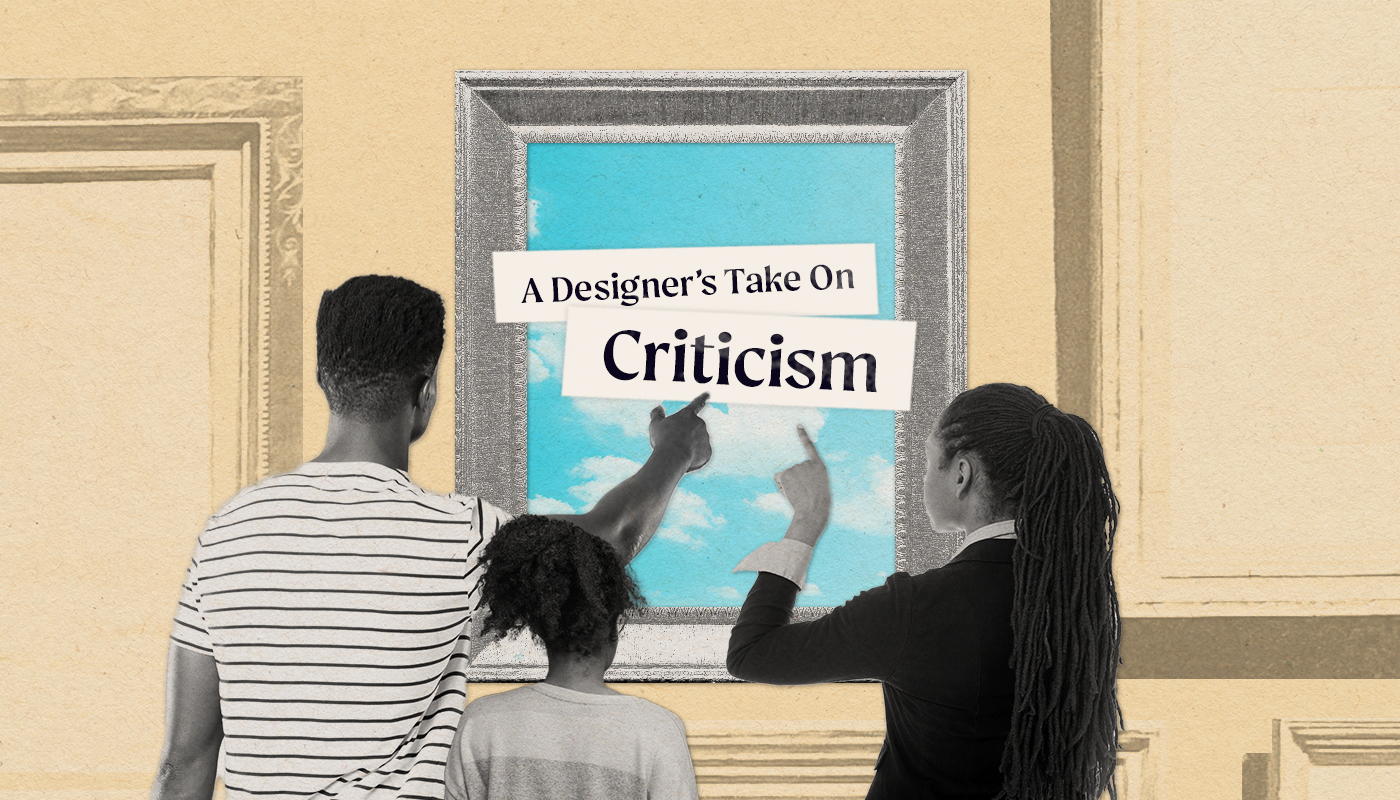

Understanding criticism through design

A designer’s take on criticism and allyship.

As a software engineer trained in design, criticism has been key to refining my work — be it in the design process or code reviews or design critiques. At a personal level, my Chinese upbringing taught me the value of criticism, which helped me polish numerous relationships into true friendships. But a quick google search reveals much contempt for it. Many self-help websites call criticism “negativity” and a source of emotional pain; some even advocate for silencing it. While criticism can sometimes be poorly phrased or even downright hurtful, shrugging off genuine criticism simply because it doesn’t appease us is egotistical and problematic, especially in the context of allyship.

What is criticism?

Criticisms are expressions that convey disapproval, but not all criticisms are the same. For example, an exposé on social media predicated on cancel culture is not the same as a criticism against an organization claiming to support disability rights while perpetuating ableism. My use of “criticism” in this article refers to feedback given to an ally by marginalized groups with the intention to stop harmful behavior.

I first encountered criticism in design school. Design criticism is a conversation where designers criticize each other’s work to improve the final product. It is such a common practice that the American Institute of Graphic Arts published their own critique guidelines. Award-winning designer Natasha Jen says criticism helps designers evaluate the merit and the quality of their work. Feedback is a key ingredient in this evaluation. It allows designers to question their own work with a different perspective, challenging them to produce evidence to support the assumptions, intentions, and research behind their work. In this way, design is similar to “allyship” in that an ally—similar to a designer—performs work for others based on their knowledge of the target audience. But if allies are helpful well-intended people, why criticize them?

Why criticize allies?

Often well-intentioned and almost always a self-originated quest, “allyship” is perhaps even more worthy of criticism than design. From pathological altruism to saviorism, one need not look hard to find criticism of allyship. In the racial context, many wrote about their exhaustion from white fragility. Others criticize allies who stand in to speak for, and misrepresent, communities to which they do not belong. In workplaces, performative allyship overshadows discriminatory practices that cut across race, gender, and disability behind closed doors. A 2021 study by Lean In titled “Women in the Workplace” reveals that of the 77% of white employees who consider themselves allies to women of color, less than half has taken any key “allyship action”, which includes advocating for new opportunities and confronting discrimination. This, coupled with the interweaving web of criticism, is evidence that allyship often falls short of its good intentions and is far from perfect, with shortcomings that have left many disappointed, skeptical, and critical.

of white employees who consider themselves allies to women of color, less than half take any key “allyship action”

It is my hope that by reflecting on my own experience, I can share a few notes on how to take criticism well as an ally:

Start with acknowledgment.

Acknowledging pain is a technique used in medicine. It is said to have enormous emotional benefits. When someone brings a concern to your attention, it is a sign of trust. Most people are inclined to avoid confrontation, so the fact that someone feels compelled to communicate their concerns implies how important the issue is to them and also the strong feelings they may hold. When they share those feelings with you, whether or not you agree with them, do not dismiss them. Acknowledgment is key.

Ask questions.

Asking questions is an effective way to defuse tension. Not only does it show your commitment to the other person, but it also gives you an opportunity to understand their perspective. Sometimes visual aids help. I am a visual person. If the situation permits, I sometimes take notes while the person speaks. Opting for a pen and paper over a device ensures transparency while reassuring them that I am not distracted. I am listening, writing down, and processing what they are saying.

Let them answer.

Once they start sharing, hold the urge to cut them off to defend yourself or to share your opinion. If an interruption is necessary because you need clarification to understand more accurately, do so politely but sparingly. Interrupting someone at every turn while they are processing and sharing their thoughts can be very distracting, making it easy for them to lose their train of thought. Taking notes can help you retrace your thoughts to share your opinion or to ask questions when they are done sharing.

Decenter yourself.

I remember when I was in design school, some of us could get very defensive during a critique. When that happened, my professor would remind us:

Remember,  this is not about you.

this is not about you.

Remember, ![]() this is not about you.

this is not about you.

Her criticism was direct and sharp, but thoughtful and precise. Like an incantation that disarms and empowers at the same time, her words quenched our burning desire to defend our ego and redirected that energy to the problems at hand. “What about the target audience?” Pinned to the wall was our work, but the subject of criticism was not how we feel. It was about how our design affects those we designed for.

From design to allyship, critique makes us better.

Besides the infinite possibilities design holds, it is a discipline similar to allyship—both are work performed on behalf of others; both require the understanding of perspectives that may not be our own. In design schools, designers are taught to research and understand their audience. Allies who stand in solidarity with another group bear similar responsibilities. According to the Guide to Allyship, an ally is able to own up to mistakes and de-center themselves. Being defensive is self-centering—the opposite of allyship. As an outsider in solidarity with another group, criticism is the only way to ensure your work is meaningful to those you care about.![]()